As we wrap up the 2023-2024 academic year, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with graduating biomedical student Brian Nguyen about his Honors Thesis “Phenotypic Characterization of 123 Genes in Bacteriophage Lebron Expressed in Mycobacterium smegmatis.”

Nguyen’s project focused on characterizing the genes in the genome of bacteriophage LeBron. Bacteriophages (phages) are viruses that infect bacteria. LeBron was discovered and identified through the Science Education Alliance (SEA)-PHAGES program at La Sierra University. To characterize LeBron, the SEA-PHAGES program first used bioinformatics to map out its genome. Through this process, students in the program were able to determine how many genes LeBron’s genome contained and what the functions of each gene were. Many of the genes, however, had no known function. Nguyen’s project, therefore, was characterizing these “no-known function” genes by determining their effects on bacteria.

Nguyen characterized these genes using two different procedures. The first assay Nguyen used was a cytotoxicity assay, in which he tested if each gene had toxic effects. In other words, he studied whether or not gene expression inhibited the growth of bacteria. He also tested whether or not the gene played a role in protecting against superinfections. Superinfections occur when a bacteria is infected with two different types of viruses. Phage genes, therefore, can have the function of preventing the infection of that bacteria by another virus.

Nguyen’s background in bacteriophage research through the nationwide SEA-PHAGES program both inspired and prepared him for his project. Nguyen was able to participate in SEA-PHAGES as a first-year undergraduate student. It was through this program that Nguyen discovered his love for research and scientific inquiry and became involved with Dr. Arturo Diaz’s lab in his third year. Moreover, his time in the SEA-PHAGES program taught him the techniques and skills he needed for his more independent research for the Honors scholarship project.

While his SEA-PHAGES experiences prepared him in many ways, Nguyen still faced challenges in adjusting to independent research. “I was so used to having everything set up for me and then all I’d have to do was put substance a into substance b or do the right protocols given all the materials given,” he said. In his Honors scholarship research, however, he had to learn how to do all the prep work, which required an entirely new set of protocols like preparing plates. Nguyen mentioned, “That was a learning curve because it took a lot of time to get used to and to be comfortable being able to do all that work myself.” This learning curve affected not only the quality of his data but also the pace at which he collected it, which led to one of his other major challenges. Initially, Nguyen planned to research bacterial protein interactions within bacteria using phase LeBron. However, given the preliminary work necessary for that original project and the pace he was working with, Nguyen ultimately had to pivot to his current project of characterizing LeBron’s “no-known function” genes.

Nguyen’s project has both clinical applications as well as general contributions to scientific understanding of microbial life. “The study of a bacteriophage in general is very important because studying them can help in the field of phage therapy in an age of antibiotic resistance,” Nguyen stated. As phage genes can express products toxic to bacteria, as found through cytotoxicity assays, phage can be used as an alternative therapy against bacteria. For his project in particular, Nguyen said, “Now we can use these characterized toxic genes to figure out how we can incorporate them into therapies and treatments. We can use them to create therapeutics and antimicrobials that help target specific bacterial components and proteins and ensure effective treatment of these diseases.” Furthermore, the study of phage can help determine the importance of cellular processes and the importance of biological interactions between bacteria and phage. “The study of phage also provides new information to advance the field of molecular biology and virology,” Nguyen said.

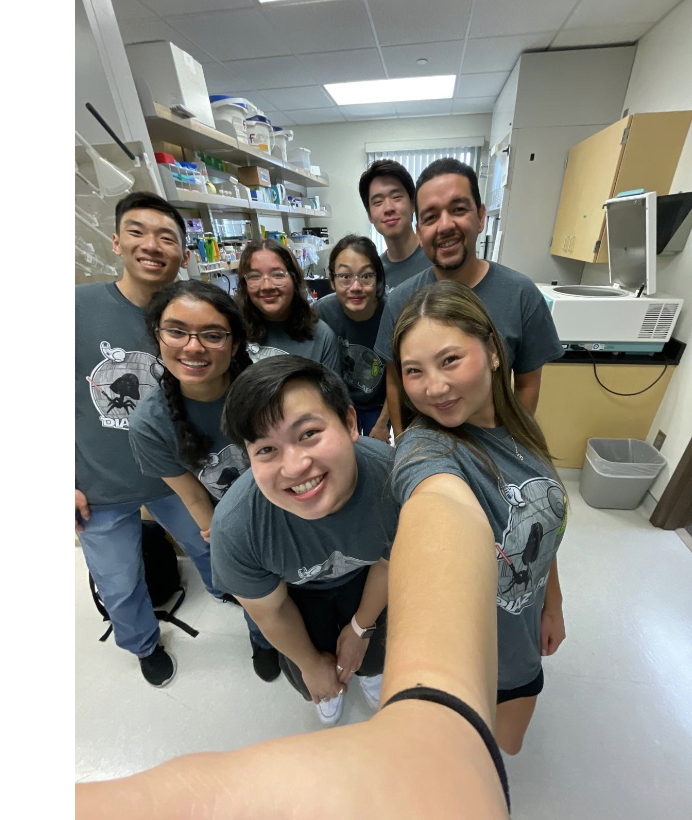

This project enriched Nguyen’s undergraduate experience, not only academically but also in terms of community. He was able to apply what he learned in the classroom setting to research that contributed to the body of scientific understanding as a whole. “My project reinforced the idea that science is a collaborative field and we’re all working together towards the same goal, which is scientific discovery,” said Nguyen. “I was able to build a sense of community with my peers and lab partners in a way that has really enriched my undergraduate experience. They have been a really strong support system in everything that I do in research.” In particular, Nguyen greatly enjoyed working with his lab partner, fourth-year biology student Earick Cagang. Their compatibility as both researchers and as friends was Nguyen’s favorite part of his project.

Nguyen’s project allowed him to characterize many of the previously undetermined gene functions of LeBron. He was able to run cytotoxicity assays on 122 of the 123 genes in LeBron’s genome, finding that 39 of those genes inhibited bacterial cell growth. Furthermore, he was able to characterize 22 of those toxic genes while the other 17 still did not have known functions. Nguyen was also to run defense assays on a 12-gene section of LeBron’s genome theorized in many phages to have an effect on superinfection prevention. One of those twelve genes was found to function in superinfection prevention.

To those looking toward research in general or their scholarship projects in particular, Nguyen emphasizes that it is okay to make mistakes. “The point is that you don’t let them [mistakes] stop you. You take them as a learning experience and you assess what could have happened, what could have gone wrong, and you just continue moving forward,” he said. “Dr Diaz always likes to say that sometimes in science and biology and research things don’t work the way that you expect them to and that’s normal. That’s just part of the wonderful world that is scientific research.” As someone who had to change his initial direction, he believes that it’s natural to hit road bumps as more research comes along. “It starts off as a proposal and your project will evolve as you gain more data or do more research.”

—Katie Jang, Class of 2025: English Literature