Despite being a small institution, La Sierra University’s undergraduate research labs have consistently given students opportunities to participate in published research. Particularly, students within the Honors Program consistently produce meaningful research each year through their scholarship projects. I had the wonderful opportunity to interview three noteworthy students from within the Honors Program about their undergraduate research.

Ester Peiro:

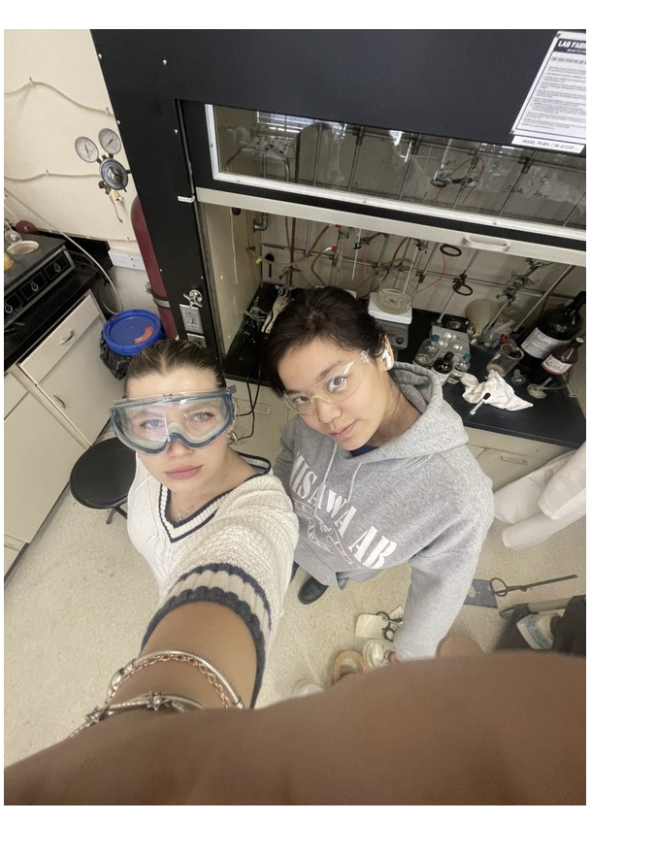

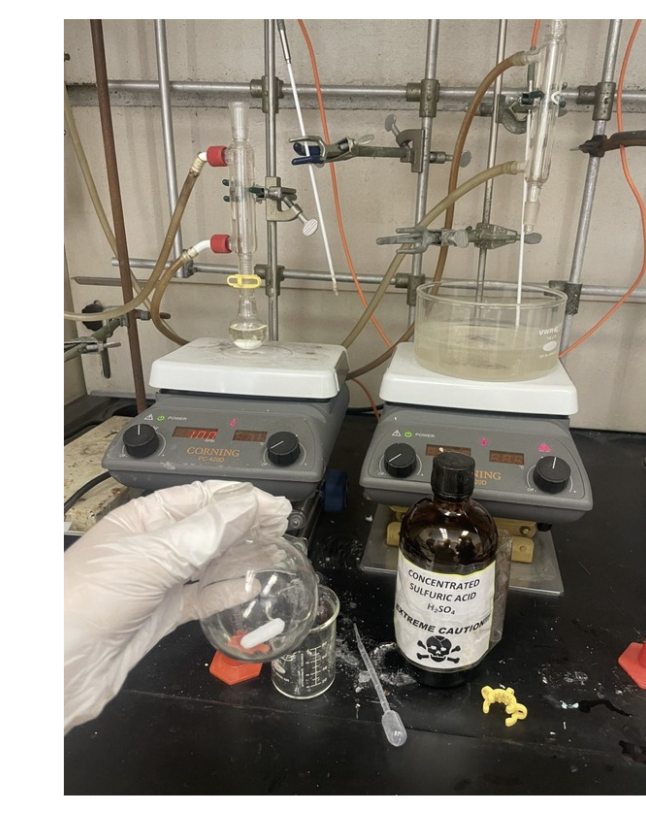

Ester Peiro is a fourth-year senior biochemistry major at La Sierra University on a pre-medicine track. Her research revolves around finding a means to synthesize alternatives to antibiotic drugs safely. As antibiotic resistance remains a prevalent issue within healthcare, researchers have aimed to find alternative methods to fight bacteria. Sulfonamide drugs are one of these alternative methods, however, their synthesis involves a hazardous reagent called chlorosulfonic acid. Ester’s research aims to replace this reagent with acetyl sulfate, a potentially safer substitute, and she aims to see whether or not this method is effective in synthesizing sulfanilamide for antibacterial drugs.

Ester first became interested in this research because of its direct application to medicine and its historical context. Sulfanilamide once dominated the pharmaceutical world, however, its prevalence fell out of favor because of its harmful effects. This potential for revitalizing sulfanamide’s prevalence intrigues Ester and keeps her motivated despite some of the challenges she has faced during the research process. She began working on this research as a sophomore without having taken an organic chemistry course, which made it more difficult for her to understand the theory behind the project initially. However, her extensive experience within the SEA-PHAGES lab with Dr. Arturo Diaz meant that she was still able to be comfortable with the manual lab procedures and had a good understanding of the practical side of conducting the project. As she continued through her coursework as a biochemistry student, she gained a good understanding of the theoretical side of her research.

Ester describes her research as a steady progression, rather than one defined by a specific “aha” moment. Initially, the project was trial-and-error focused, with the only goal being to figure out if the first step of the reaction worked. Once the first step worked, she made a large batch of the first reaction stage, purified it, and then tested it using NMR and IR methods. In her words, “I got very comfortable with the process,” which is Ester-speak for “I had to repeat this over and over again.”

Although she admits research can be a monotonous undertaking at times, she urges other students to get involved with research on campus. In her words: “If you are interested and curious about something, follow it. Do not hesitate to ask a professor about their research, they will probably be enthusiastic about it. You are not too dumb for research, no one knows what they are doing until you try. Be open to failure because you will experience it and learn from it, it will all be worth it in retrospect.”

Daphne Prakash:

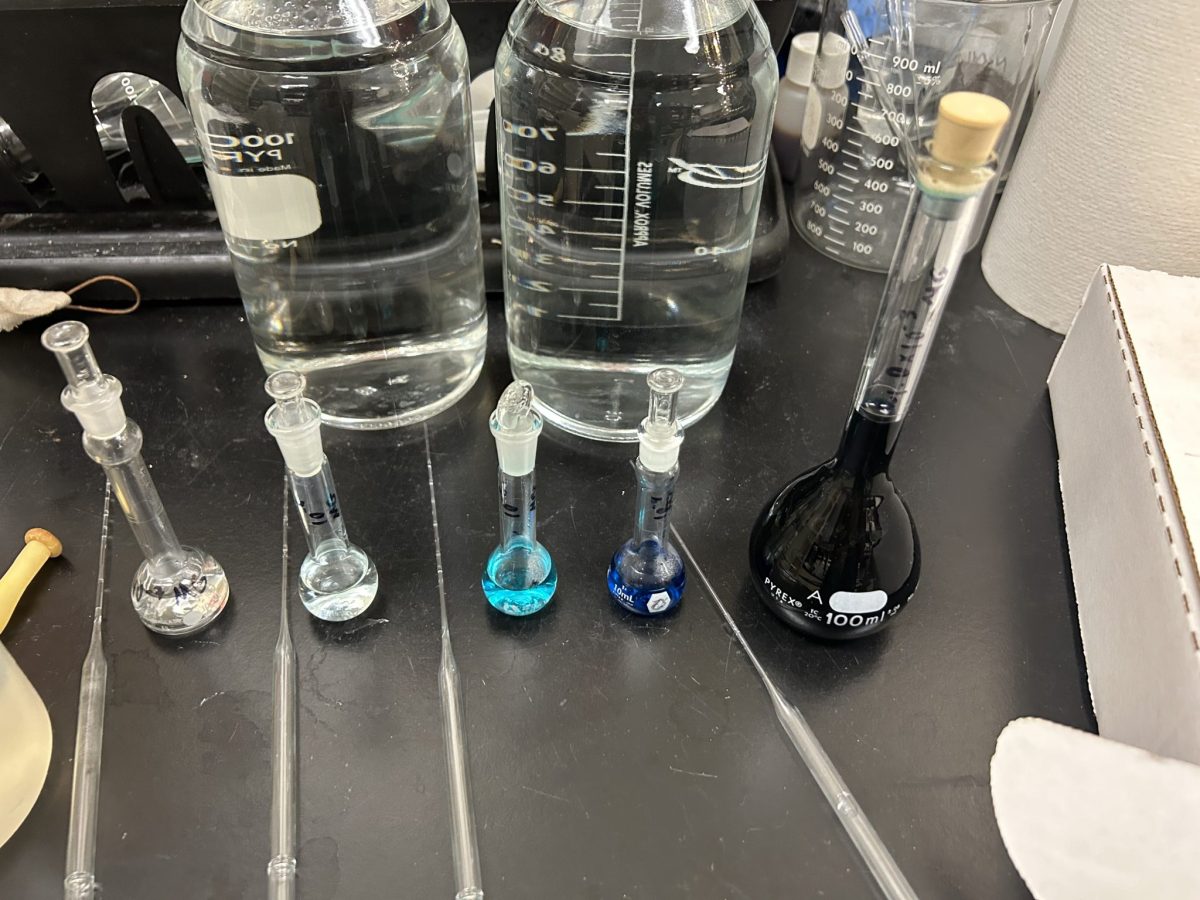

Daphne Prakash is a fourth-year biology and biochemistry major at La Sierra University. Her research involves looking at the effect of ionic strength on the chemical degradation kinetics of methyl green under basic conditions. Chemical kinetics is all about how fast or slow a reaction occurs and the factors that influence it. Methyl green is a well-known, positively charged dye that changes color from blue-green to clear when hydroxides are added to it. Daphne’s goal is to measure the time that this reaction takes while accounting for ionic effect and determine rate constants to control and optimize the chemical reaction.

She became interested in methyl green after Dr. Marco Allard approached her to fulfill a class requirement for her major. Not being one to turn down an opportunity, Daphne excitedly jumped into the project and was able to quickly learn more from Dr. Allard. Her biggest challenge so far has been controlling for ionic strength and she describes it as “a nested Russian doll problem from hell.” By the time one factor has been controlled for, multiple others appear that she hadn’t considered before. To add to the frustration, each new factor needed to be accounted for in order to produce a pure final product.

In spite of these challenges, Daphne remains committed and excited about her project’s end goals and potential upsides. She describes an “aha” moment that came while she was presenting a research proposal on her project. Presenting the proposal forced her to take a step back and explain her progress thus far, which put into perspective how far she had come and how much knowledge she had gained during the process.

Daphne credits much of her understanding to the Physical Chemistry course that she took with Dr. Allard last quarter. Working with him in a classroom setting as well as in the lab has given her an outlet to apply the knowledge she has learned, giving her a twofold advantage. Physical Chemistry taught her the importance of kinetics as she began to get deeper into the topic as part of her research. She also credits other courses, like Molecular Science, in teaching her how to be a better communicator and receive feedback from professors and peers on how to communicate her work more clearly. She believes that scientific literacy and being able to read papers or do research and explain what is happening in simplified terms is something that every researcher should be able to do and is extremely valuable.

She offers this advice for students looking to get involved in research: “Get in touch with your professors and learn more about what they do! I’ve been really lucky in the sense that research is something I’ve always been interested in, but there wasn’t any specific topic that I was focused on, which led to opportunities in different labs.”

Julia Ko:

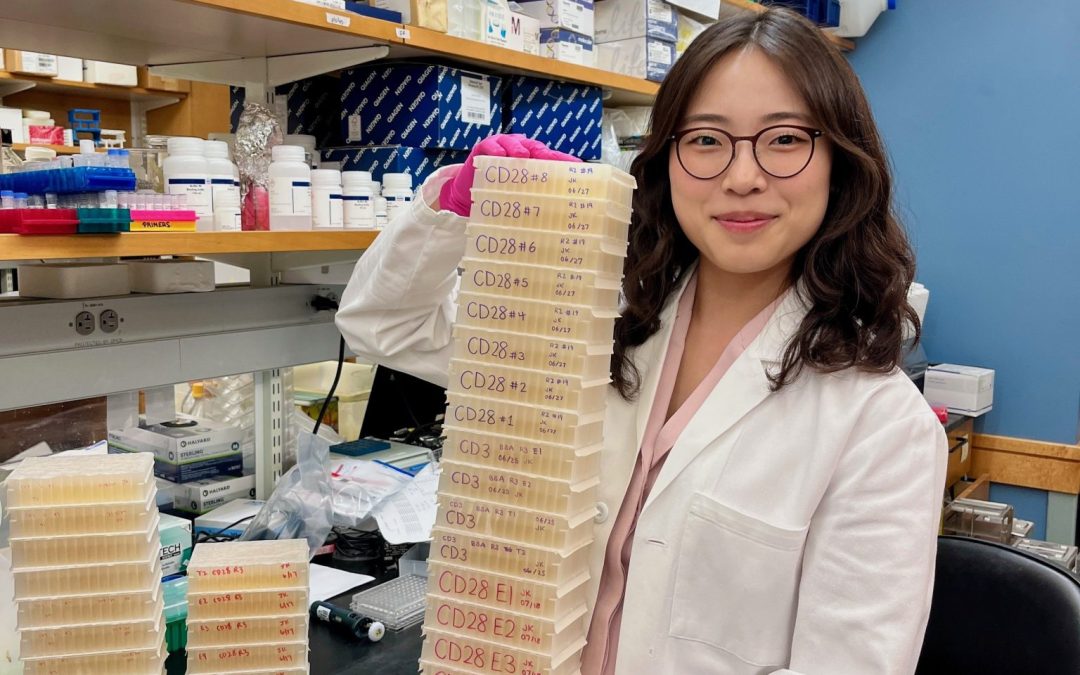

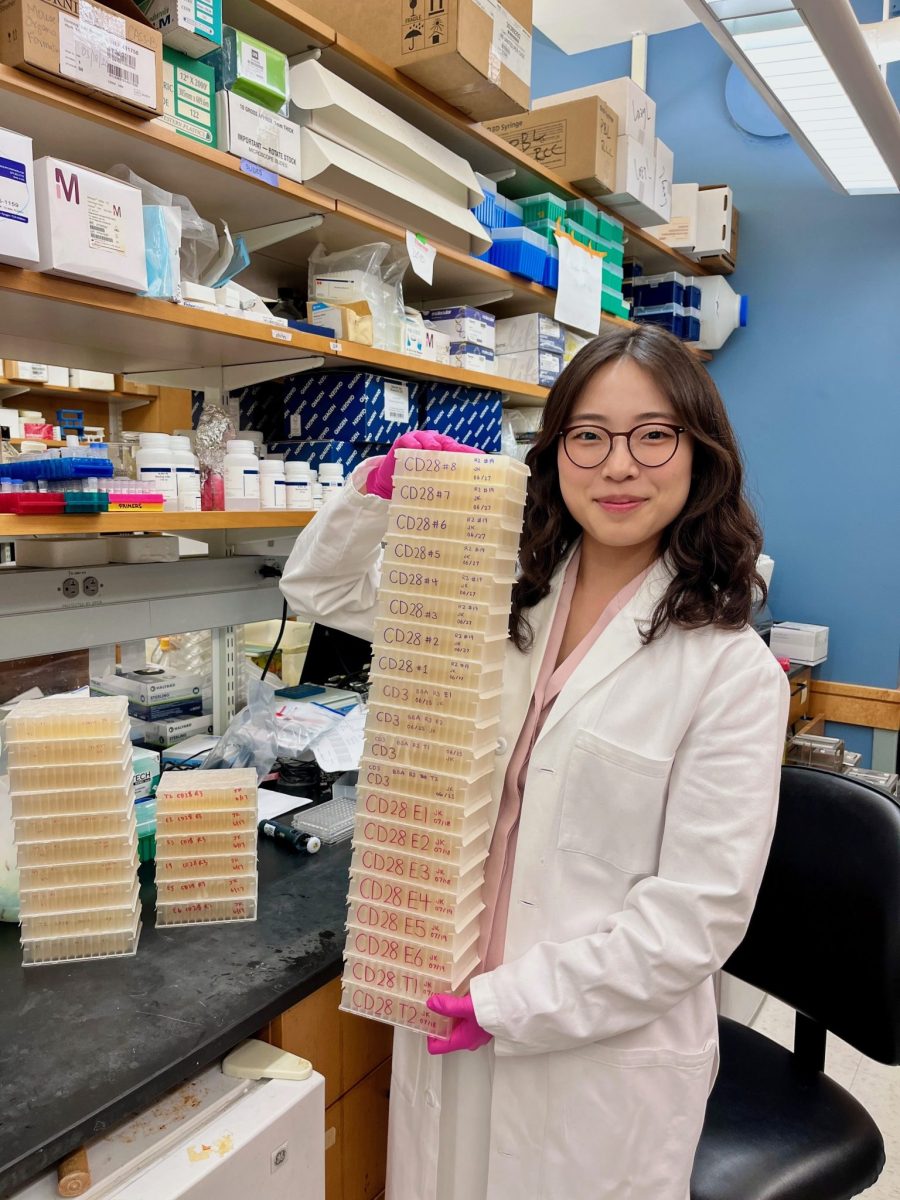

Julia Ko is a third-year biomedical sciences major on a pre-M.D./Ph.D. track. Her research centers around finding a novel antibody candidate that activates the immune system to target cancer cells. In her words, “Imagine The Hunger Games, except the contestants are antibodies and I’m President Snow. That’s essentially my research in a nutshell—screening billions of antibody candidates to find the few elite ones that can activate T-cells and help the immune system fight cancer.” T-cells are a type of white blood cell that play a central role in the immune system in recognizing and destroying infected or cancerous cells. Julia’s research focuses on discovering a new antibody that will target two crucial surface proteins on T-cells: CD3 and CD28. CD3 and CD28 work in tandem to trigger the immune response and fully activate the T-cell to prevent it from becoming unresponsive. Current cancer immunotherapies already target these pathways, but they face issues such as poor specificity or harmful side effects.

Julia worked in the Marasco Lab at Harvard’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute using Dr. Wayne Marasco’s proprietary phage library containing over 27 billion antibodies. Using techniques such as phage panning, ELISA, and biolayer interferometry, she screened and characterized antibody candidates for high affinity and specificity to CD3 and CD28. She also carried out bacterial transformations, mammalian cell transfections, and IgG purification to prepare for downstream functional testing. Julia has been able to identify a promising anti-CD3 antibody that she plans on testing in an in vitro T-cell activation assay. If this is successful, that candidate could contribute to safer, more effective cancer therapies by helping T-cells overcome the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and carry out their mission more successfully.

“Just like in The Hunger Games, only the strongest antibodies make it out of the arena—and the one that wins might just help save lives. May the best binder win.”

Julia’s interest in cancer immunotherapy research stems from a personal place – her father’s cancer diagnosis when she was in high school. Watching him go through treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic made her realize just how powerful medicine could be, not only in extending life, but in restoring hope in chaos. That experience motivated her to pursue research that could help improve treatments for patients like him. When she was accepted into the Harvard-Amgen Scholars Program and joined the Marasco Lab as a summer intern, she was drawn to their work on antibody discovery for cancer immunotherapy. The lab’s focus on translational research felt like a perfect fit, combining her scientific interests with her desire to make a meaningful impact.

One of the biggest challenges Julia faced in her new environment was imposter syndrome. She was the youngest and least experienced person in the lab, surrounded by Ph.D. students and postdocs who all seemed to know exactly what they were doing. She felt like the new kid on the block and at first, hesitated to ask questions or contribute during meetings out of the fear that she would say something wrong and embarrass herself. But she realized that feeling didn’t necessarily mean she didn’t belong – it meant she was still growing. She started speaking up more and taking ownership of her learning. Julia credits that shift to helping her grow not only as a researcher, but also allowing her to bond with her classmates and find her voice.

Julia’s most recent “aha” moment happened during the summer she spent in the Marasco Lab at Harvard. “It was past midnight, and I was in the biosafety hood transfecting Jurkat cells with plasmid DNA. Despite the exhaustion, I felt completely absorbed in the work. I wasn’t thinking about how late it was or how tired I felt—I was just in the moment having fun. That’s when it hit me: if I could genuinely enjoy this process under these conditions, maybe this wasn’t just a summer research project. Maybe it was a preview of the life I want to lead. That realization hit me hard because up until that point, I had always questioned whether I truly belonged in research, especially in such a high-level lab. But at that moment, something shifted. I saw myself not just as a student completing a checklist of experiments, but as a scientist in training—someone who could thrive in this environment and love it, even when it was hard. It gave me a glimpse of what a future as a physician-scientist could look like: driven by curiosity, built on late nights and driven by the joy of discoveries that have the power to heal. That night and many moments like it reminded me why I want to pursue an M.D.-Ph.D.—to bridge the gap between bench and bedside, fueled by both scientific wonder and a desire to improve lives.”

She had a similar “Eureka!” moment while taking Cell & Molecular Biology (C&M) with Dr. Diaz during her sophomore year. Prior to the class, her knowledge of cells was a collection of memorized facts without a comprehensive understanding of how everything was connected. C&M changed that for her. Suddenly, she was able to visualize the cell, fit each fact into its place, and see how they fit into the bigger picture. Julia credits cell biology as being one of her greatest interests and hopes to continue work that is tied to it.

Julia offers this short piece of advice for those interested in participating in research, “Try lots of things, and pursue what you love doing!”

—Eddie Nguyen, Class of 2026: Biology/Pre-Dentistry